Comment:

The five challenges to religion by the natural sciences as outlined by Ames and Camilleri are important and require careful and thoughtful responses from those of us professing religious convictions (in my case, Christian).

Let’s talk about the fifth challenge. This results from the view that an adequate philosophical position is provided by the natural sciences. Further it implies that the only reliable knowledge is provided by science. Let’s be clear. This is a worldview that ignores the fact that there are underlying metaphysical assumptions involved in doing science. For example:- the rationality of the world we investigate; our capacity to interrogate that natural world with the methods of science; while our knowledge is always incomplete, it is not meaningless. But such metaphysical assumptions, and others also needed, actually lie outside science [a point made forcibly many years ago by the late Sir Peter Medawar, though not a religious person himself].

So what is involved here is a worldview that bases its position on the primacy of science. To be able to respond from an informed religious perspective, Ames and Camilleri express the hope for constructive mutually critical conversation. As a practicing Christian and professional scientist for well over half a century, I have always found it liberating to understand that faith and science can be understood in harmony. But what stands against creative conversations is the difficulty of establishing a common vocabulary and the associated difficulty of teasing out the assumptions underpinning different points of view.

These days there is an extensive literature at the science-religion interface which provides fuel for the kind of creative conversation Ames and Camilleri would like to see. Perhaps most important of all is the need to listen in such a way that one grasps what people mean, not just what they say.

John Pilbrow

Emeritus Professor of Physics, Monash University

Opening Comments From Chairs

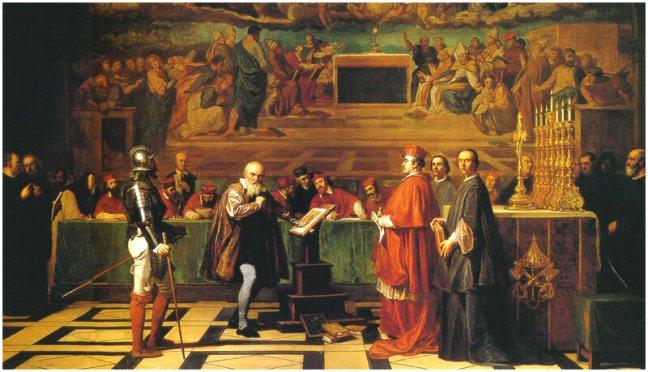

A common view is that there is an inherent conflict between science and religion. This can take the form of an historical claim. It has become almost a throwaway line to support this claim by pointing to the treatment of Galileo by the Catholic Church in 1632. Yet much recent historical scholarship has now challenged the view that this episode is representative of the ‘inherent conflict’ between science and religion.

Historically, religious concerns guided the science of Kepler, Newton and many other pioneers of the Scientific Revolution. For them, studying the universe demonstrated the attributes of God. This view was eventually replaced in the 19th century by radically different ones: to some science and religion are necessarily antagonistic, to others they belong to separate realms, while others still see a mutually illuminating consonance between the two.

The perceived conflict between science and religion is fuelled by at least five challenges to religion from the natural sciences. The first concerns the belief that the universe has been created by God for some purpose. However, according to the natural sciences the universe operates according to blind natural processes, which reproduce the appearances of design and demand no reference to any purpose.

The second challenge is the problem of natural evil. The universe has so many natural processes (no human agency involved) that are contrary to what we should expect to find if the universe was created by an all knowing, all powerful, perfectly good God. Attention is focused on particular natural processes (e.g. tsunamis, genetic disorders, extreme weather events - before human contributions were a serious factor) and more generally the suffering and death in the evolution of life.

The third challenge is a conflict between faith and reason where ‘faith’ is taken to be belief held in the face of contradictory evidence and reason is commonly seen at its best in scientific inquiry that yields evidenced based beliefs. It seems obvious that embracing a scientific approach to the world must rule out such ‘faith’.

The fourth challenge might be seen as a particular example of the third but it figures in many discussions of ‘science and religion’ that it deserves separate recognition. It is the tensions between the scientific view of the universe and the very different view presented by Sacred texts, for example the account of Genesis we find in the Old Testament. At best the Bible is seen to be outdated for anyone with a scientific view of the world.

The fifth challenge is a philosophy that is based on the natural sciences, and is often identified with the natural sciences. It makes two claims. One is that the only way to find out about the world is to use the methods and standards used in the natural sciences to justify knowledge or rational beliefs. The other is that all there is, is what the natural sciences say there is. On this view, the totality of existence is reducible to what physics says there is, or complex configurations of the same.

Two of the places where this shows up is in the scientific explanation of religion and in the assumption that human consciousness is entirely produced by brain processes. But this in turn raises questions about the extent to which moral judgements, or purposive action more generally, can be understood from the perspective of a ‘naturalistic worldview’.

Theological and philosophical debate continues over these challenges. It is easy to find an inherent conflict between fundamentalism in religion and say scientific naturalism. But this does not mean there is an inherent conflict between science and religion. It is possible to be a practising Jew, Christian, Muslim, Buddhist or Hindu and be a practising scientist.

On the other hand there are indications that other levels of reflection are engaged. Steven Weinberg has said that the more we understand the universe the more pointless it seems, but then goes on to say that only scientific inquiry raises our existence from the level of a farce to that of tragedy. Yet if we reflect carefully on Weinberg's remarks, it quickly becomes apparent that this ‘raising’ is no small shift, and one wonders what it is about human inquiry that Weinberg thinks gives it this power. Moreover, one may well ponder whether the so-called ‘ultimate questions’ dealing with the meaning and significance of human existence can be satisfactorily answered by secular intellectual traditions.

An alternative to the idea of inherent conflict is the possibility of a constructive mutually critical conversation between science and religion. To illutrate, might not science and religion find common interest in the remarkable phenomenon of human inquiry and whether such inquiry could be ‘placed’ in any world view; in promoting science as a worthwhile vocation; in examining the scientific and philosophical presuppositions of economics; in challenging the cultural roots of the anti-science attitude, that has appeared, for example, in many of the sceptical responses to climate change.